This final post in the “Learnings from Scaling a Product Engineering Organization to 280 People” ties all the first principles together around the six dimensions of a product operating model.

Back in late 2024 when I wrote the first draft of this post, I had moved into my new role as Chief Product Officer at Omny Security heading the product organisation (engineering, product management, and design). One of the things I reflected over coming into the role was how hard it is to know the expectations to product leader roles and that the title doesn’t really say that much. When looking for a role, the profiles, skills, and personal ambitions of the CEO and the other leaders are much more important. A late 2024 ChatGPT version illustrated the problem as below (yeah, it’s only a year ago!).

Independent of how your role is set up, as a product leader you are responsible for building great products that customers want to buy that works for your company. This means you need to set up your organization to succeed on the six important dimensions that I have described in this this series (start here if you want to read in chronological order). Together these form a product operating model ( or “product model” for short as Marty Cagan refers to).

The product model can be implemented in many different ways, just look at how different Apple and AWS build products. Obviously, there are some first principles that need to work, and a model that works is consistent across the six dimensions:

- how you ensure focus on the value to the customers,

- how product priority decisions are made,

- how you communicate and give teams enough context,

- how code and people dependencies are managed,

- how you ensure things are built the right way for long-term success, and

- how things get into production and into the hands of the customers

I have pointed out in earlier posts how easy it is to get into discussions about how to build product the “right” way. The awareness of the first principles of building product is low in many organizations (outside Silicon Valley and a few pockets of tech product density). Without having experienced first hand how to build product, people resort to methods, processes, roles, and rituals that they either bring with them from their previous jobs or have read about. They are then implemented without understanding the WHY, and you end up with what Cagan calls “product theatre”. And even worse, incompatible processes, roles, and rituals can be introduced across teams and functions, thus making it very hard to collaborate. Let’s look at each dimension.

Ensure Focus on Customer Value

This dimension is one of the trickier ones to get right, and if you get it wrong, you will definitely build the wrong product. The most important first principle is that you need the entire product team to deeply understand how the customer gets value out of the current product and what additional value to add. What is often lost is what “deeply” really means.

Imagine that you hire a sculptor and tell them that you want a sculpture in marble showing a man and a child playing. What do you think you will get? In order to make the sculpture, the artist needs to shape two faces, decide on ages, length of hair, type of hair, body type, activity they will do, and a thousand different things. Let’s say you are a known soccer player, then the sculptor may assume you want them to play soccer. This is exactly the same thing that happens when a product team is asked to build a feature or solve a customer problem without having a way to deeply understand how to shape that feature.

There is lots of literature and content on the web that teach you how to do product discovery. However, for your operating model, you need to figure out how to set up your organisation in such a way that you connect the product team with the users and the customers of the product. They need to iterate over time to deeply understand what the details of a great product solution to their problems should be. In a B2B startups early phase, this is basically the same thing as selling, so you need the product team to sell. Rob Snyder at Harvard Innovation Lab has some great resources on how. If you don’t force the product team to sell, the sales team will dream up a product (since you don’t have customers yet and you don’t have a product either). In B2C, there are many great approaches to being close to the users. One favourite of mine is how Rahul Vohra did it with Superhuman. If you have customer success, they are part of the product discovery process as well and need to understand how to engage with the customers together with the product teams. And as you grow, you need to find ways to establish good feedback loops. Customer advisory boards, beta programs, co-development projects, quarterly product strategy engagements with key customers, and a good proxy metric for value are all examples of useful tools. Most B2B startups fail because product doesn’t get close enough to customers and as a result the product does not give the users and the customers enough value.

If you think this sounds like customer-driven product development, you are partially right. One half should be customer-driven. The second half should be a strong product vision. If you don’t have a strong vision for the problems you want to solve for your customers and for how to solve them, you will find so many dead-end problems to solve that are not part of a scalable product. The story of the strong-minded product visionary who builds something without deeply understanding the customers’ problems is a myth.

If you are unable to get focus on customer value, the five other dimensions are almost irrelevant. I suggest a one-page product strategy and one key metric for value as the place to start driving focus on customer value.

How to Make Product Priority Decisions

A product team needs to make the following decisions: which customer problems to tackle, how to solve the problems, and how to build the solution to the problem. In the early phases of a company’s life, there should be one product team and they should be selling, delivering, and building the product.

Each of these three need some guardrails (“don’t go outside here”), some principles (“this is our approach”), and some guidance (“here is what we prefer”).

Being an empowered product team does not mean that the team should independently choose whichever customer problem they want to solve. In fact, if you have multiple teams working on the same product, you want to ensure that all the the potential problems to solve are evaluated and prioritised together. Also, you want to ensure that the problem, the solution, and the implementation are evaluated as a whole (probably multiple decisions as you progress in discovery). You can then see across all the teams to make a decision for which problems to prioritise for a given time period. Some companies do this in a product board or through a consultative process with key stakeholders. The most important is to ensure that that there is a continuous decision process where the organisation is able to make important trade-off decisions.

Inability to get close enough to the customer and focus on customer value will inevitable show up as product priority decision problems. But don’t introduce complex processes and artifacts for making decisions until you have nailed how to get the organisation to focus on customer value.

How to Give Teams the Right Context

Most startups and scaleups struggle with communications and as a result give their teams too little context to make good decisions. In the table below, I summarize the typical context needed along the three types of guardrails introduced above.

| Guardrails | Principles | Guidance | |

| Which problems to tackle | Product strategy | Product principles | Themes or initiatives |

| How to solve the problem | Key metric(s) | Core product capabilities | Frameworks |

| How to build the solution | Internal tech stack | Inner and outer loop + release cycles | Review processes & docs |

If you put in place artifacts, training, clear expectations, and consistent communications for these nine categories of context, you will get higher velocity in the teams and better outcomes. But remember, less is more! Out of the guardrails, things the teams should not deviate from, I covered product strategy and a key metric above. The third guardrail for how to build the solution is the tech stack. Your tech stack does not only include the languages, frameworks, and tools you standardise on, but also any internal services, design system, logging, metrics, tracing, and other technical components built or integrated to increase productivity. Make sure your tech stack is simple and that you don’t solve problems you don’t have.

Then to the product principles. these are strongly articulated rules that should not be deviated from without justification:

- Product principles are rules about the type of problems we want to tackle, for whom, and how we frame the problems. At Omny Security, we service customers who own large physical infrastructure or production assets like oil and gas installations, and a product principle is that we prioritise customer security problems that can be solved better by seeing them in the context of our customers’ operational processes (which we are able to do much better than our competitors).

- When we solve problems, one of the core product capabilities we use is storing the data in a rich security digital twin representation of the customer’s operational security. Another example would be a generative AI capability that can be leveraged across many different problems.

- Building the solution requires the team to collaborate on problem and solution discovery, as well as detailed UX and UI design and coding. This happens through the inner loop (the individual engineer’s process working on the code), the outer loop (collaborating with the team on corrections, getting reviews, and getting the code into production), and the release cycles (iterate and improve).

Note how the guardrails and principles should be fairly stable and with a fairly long horizon, typically 12 months. You want to have mechanisms in place to continuously revise guardrails and principles, but if you suddenly throw some of these over board, you need to plan for a productivity hit.

Finally, guidance should be more dynamic, and the proposed guidance may be different for you than the ones I have suggested. An example of a product priority guidance is the use of themes or initiatives for a planned release. Using these, you can guide the teams to prioritise resources in the targeted directions. Similarly, to guide the teams on how to solve customer problems, a typical guidance is the introduction of a framework for how to reason around certain problems. These can be generic frameworks, like Jobs To Be Done and customer journeys, or a more custom developed framework that you create for a class of problems. But don’t introduce a framework for the sake of adopting the framework: cherry-pick what can work for you to solve the needs you have!

Another to establish guidance for how to build the solution can be to have review processes for UI/UX designs as well as for architectural decisions, e.g. through a Request For Comments/Architectural Decision Record process. Other types of guidance can be related to code reviews, like Google’s review practices.

Whereas guardrails and principles are focused on WHAT is actually produced, the guidelines are typically focused on HOW things are produced. When determining what kind of context needed for your organisation, you need to consider your size and maturity. In particular, consider how formalised the context needs to be communicated. However, even the smallest startup should have an awareness of how a shared context is established. Senior product people typically do this without being asked, but in most cases you should establish an agreement on the minimum. Also see my post on What Good Looks Like for an approach to getting agreement on how you work.

How to Handle Dependencies

I covered dependencies quite thoroughly in part 4 of this series. This is an area that typically evolves dramatically over time as you grow and will have a huge impact on your velocity. In the post I suggested three main approaches to handling dependencies when you grow: customer-supplier relationship between teams, program manage dependencies, and establishing virtual teams with members from teams owning code bases you need. Of course, in the beginning when you only have one team, you have one backlog and a very simple tech stack, so dependencies are resolved with individuals talking to each other ad-hoc.

A very common mistake is to allow too many languages, tools, and infrastructure work in the beginning. The golden rule is “the simpler the better, and don’t fix it unless it’s broken.“

As you grow, you should keep the tech stack as simple as possible to ensure that everybody can contribute code everywhere. When you reach the limits of this, a typical pattern is to introduce internal platform teams that offer the other teams a simplified set of services to use (i.e. a customer-supplier relationship). This way you can avoid that you have too many dependencies across teams when building new features. However, the more sprawling tech stack you allow, the more you end up with siloed code bases that only some engineers are able to maintain. Your dependency handling is also tightly related to how you make product priorities and ensure customer focus, so product management, engineering, and design need to collaborate closely to set up processes that work.

How to Build Things the Right Way

Building things the right way is typically seen as an engineering problem. This is of course true, but few people realise how elastic the time spent on a new feature can be. When engineering a new feature, it can be made to solve the isolated problem in the simplest way or it can be built to be extendable, maintainable, scalable, leverage existing investments, be reusable by others, interact with other features in the product, be usable by the user (think Apple design), and many other characteristics. Also, the implementation can be made more or less “future proof” based on what the engineer may assume about future asks.

Typically, engineers with little context for how the feature will be used or how it may be extended in the future will hedge by building the feature more robust to anticipate future asks and thus increase the time to customer value dramatically. And if they are used to being put on new things all the time and never get time to fix tech debt, they will try to build things more robust than you really need right now.

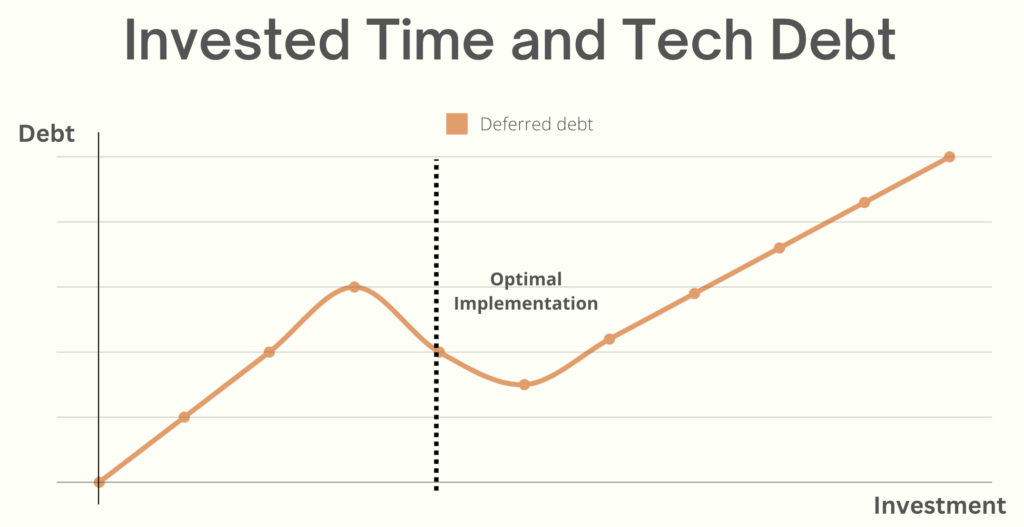

In the chart below, I show a typical relationship between time invested in building a feature and the technical debt that is built up. Let us assume there is an optimal implementation that can be chosen (impossible to really find, but the ability to find the sweet spot is a typical thing that comes with seniority). The dotted black lines shows this point. At this point, the engineer has chosen to invest just enough time to make the feature useful right now, while also made such that all the future work on this implementation will have low costs. Of course, as the future is not known, this is impossible, which is why building things the right way is so hard.

In the beginning of the implementation, some prototyping will typically be done with very limited debt created. Then, if the implementation is done quick and dirty without any guardrails, principles, or guidance, the engineer will be done at the first maximum. The entire implementation will be technical debt as everything is likely to have to be written from scratch to be integrated into the rest of the product and ready for scaling. However, if you have the right guardrails, principles, and guidance in place, the engineers will optimise implementation based on these. Implementation time will be slightly longer, but you are ready for enhancements and scaling.

However, it is common that junior engineers (and some senior ones) try to foresee future needs, and they will be tempted to immaturely solve future problems. Unfortunately, in this case the entire feature likely needs a more complicated software design, so instead of doing something simple that works for now and then refactor later, the junior engineer will create more complex code that is harder to enhance and maintain. The life-time cost of 50% more and complex code in your product is not linear as every single change will have a higher cost, and the cost accumulates.

If the optimal implementation point has been found, you will likely have a series of potential code improvements that are not strictly necessary now, but that will reduce your debt. Postpone them until they are really needed. You don’t know yet if you need them. The main take-away from this section is: rich context is critical to finding the likely optimal implementation. The second take-away for your operating model is that you need to ensure that all teams have the support they need from experienced engineers.

With AI-assisted coding, we see an increase in the number of code lines produced per engineer. We also see the number of errors and tech debt go up, especially for junior engineers. “AI slop” coined to describe bad code, abstractions, and wieldy solutions introduced by an AI agent is really deferred tech debt.

How to Get Things Into The Hands of The Customer

The final dimension of the product operating model is how you get the solution into the hands of the customer. There are three parts to this: 1. how to quickly validate that the solution offers the value the customer desires 2. how to reduce the time from the team understands the problem to a solution is available to customers to use and 3. how to get feedback on the solution so you can iterate.

This dimension is where AI tools offer incredible help if you are able to tighten the feedback loops!

The last part is crucial: ITERATE! Too many product companies believe that their roadmap should be a series of features and when they have shipped one feature, they should just move onto the next. Building great product is about delivering the desired value to the customer, not features. Sometimes you need to rip out features, totally redesign them, or evolve them systematically over time. Sometimes you fail entirely on the first attempt. Without having an operating model that focuses on the actual derived value of your product, your product organisation will just become a feature factory.

Part 1: quickly validating the solution you have come up with is actually sales in a company’s early phase. Later on as you get more customers, it becomes part of a customer success function. And when you are scaling up, it is entirely the product management organisation’s responsibility.

Part 2: reducing time from understanding the problem to having a solution available for use is primarily related to execution in the product organisation. For a young company, the key to success is to break up the solution into smaller usable components that can be shipped quickly. What is the time from conceiving a solution until you have data that verifies that the customer got the value you intended and is happy?

Part 3: how to get feedback and iterate is tighly connected to the product priority decisions and the key metrics you use. You are not done when a feature has shipped. How do you ensure that learnings from the new feature is fed back into the prioritisation process?

So, again, look at the phase of your company and what is critical to get right. What is your cadence and how do you engage with customers? How are you set up to make product priority decisions? How are insights from how your customers engage with your product fed into the prioritisation process? If your product organisation is out there doing interviews with people who are not customers and not part of the sales process, something is wrong. Pre-product market fit you are both building product and finding the “right” customers. You run the risk of building the wrong product and/or selling to the wrong customers. Very early in this process, you need your product teams very close to the customers. Product teams in B2B worry about overfitting to a single customer. I recommend taking the cost of overfitting. High product velocity and iterating on the product will help you find the right product as long as you keep engaging with new customers to discover their problems (some people call this sales). Keeping the feedback loop short is extremely important and any attempt at scaling anything should be resisted.

The iteration speed of getting the product into the hands of customers and validating value is the single most important factor of the success of a product company in the early days.

Wrapping Up

Building great product is hard, doing it in a startup is even harder. In the first article in this series, I shared my four key learnings from Cognite: you are always on your way to the ideal organisation, focus on building processes and culture that allow continuous change, optimising for velocity and for scale are conflicting goals, and you need a coherent operating model for how you build product. Using the six dimensions of the operating model should allow you to reason around how you need to change the organisation as you grow.

I have in this series tried to capture the most first principles I have learned over the years of building product in B2B software. Each first principle is simple, but how they interact and all the ways you can go wrong, are not. Hope these articles can inspire and help you avoid some traps!

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts